IT MATTERS

A treatment for Buckner International,

a global adoption agency. A candid look

at 3 real kids whom Buckner found

and their paths out of abuse.

The opening scenes...

Intro (:45)

Narrator: In a perfect world, there is no Buckner International...

Pix: Night, interior, bedroom, 5 year old girl reading. POV CU of an open, beautifully illustrated book. As she reads, the girl whispers the words on the page. (loud noise from something thrown) Her book drops. Cut to MS girl curling under blanket. (man and woman screaming. "I didn't want the damn kid...you did!...") Cut to WS from behind bed toward the door, barely open. Her bedroom is a mess. (racket escalates)

Narr: 19 out of 100 kids grow up in abusive or broken homes. It's not their fault. Some never escape.

Pix: WS continues. Girl runs to the door. She closes it, image goes black. (racket fades to silence)

Principal 1- Stephanie. A 32 year old photographer in her studio. (3:00)

PIX: Day, interior. CU of giggling child as seen through a still camera's viewfinder. MS Stephanie's leans from behind camera. Subsequent shots establish the location and how Stephanie sets a cheery mood for her subject. (nat sound in bg)

Stephanie: Photographing kids is always such fun. Cute just comes naturally. All I do is set the tone. I adore them because they're so innocent and trusting. You pray that someday they find what makes them special. But you never know, do you...

PIX: Day, exterior, suburban. WS lock-off of 4 year old girl standing alone, silently looking at the camera, with Buckner facade deep in the background. Dissolve, add 2 children per VO cue. (nat sound in bg)

Stephanie: My beginnings were what you'd call broken. When I was around 4 years old, I was placed in a Buckner home, along with my brother and sister. My mother put us there. She knew she couldn't raise us...

PIX: Night, exterior, urban. Street where streetwalkers frequent. POV inside a moving car as it drives slowly. Through the window we see shadows, ladies of the night, awaiting business. (nat sound in bg)

Stephanie: My mother was a drug addict and maybe a prostitute. Her childhood was a mess, too, so I don't really blame her...

PIX: Night, exterior, prison. WS dolly back from outside barbed wire fences. (nat sound in bg)

Stephanie: I don't have any memories of my father from when I was little. See, he was in prison back then.

PIX: Night, interior, home living room. MS from side of unidentifiable man with laptop computer. (nat sound in bg)

Stephanie: No one told me that...I found out later he was into child porn...

PIX: Series, interior & exterior. Camera roams, close to the action. No wide shots. CU and MS of kids receiving grownups' attention while they play, socialize, make stuff. Faces of adults and children are seen in 1/4 profile or from behind. They respond to each other and to guidance. ECUs of gestures. Nothing effusive or exaggerated. (nat sound in bg)

Stephanie: For the next 4 or 5 years, Buckner gave us what no one else who would, or could... My brother wasn't much of a talker...still isn't...but they never gave up.

PIX: Day, exterior. WS lock-off echoes the earlier scene with kids in front of Buckner. Stephanie and 2 siblings, now aged 7-11, are standing and looking at camera. One by one, they're taken away, e.g., in a car or holding a grownup's hand. Dissolves keep the environment static. (nat sound in bg)

Stephanie: Eventually, of course, we all left Buckner. My sister was adopted. I went to back live with my mother. My brother...moved back in with Dad...

More...

Ted Samore ©2015

SENTINEL

Filming in Iran put me

face to face with curiosities.

It’s gone 2:00 in the afternoon and despite three hours of driving, it feels like we haven't moved. One reason is the desert plateau is spectacularly unchanging. A second reason is traffic.

"They should all stay home, along with their mullahs," are the first words spoken in twenty minutes. They're from our driver, Khalil Afkhami, a respected architect in Tehran and the leader of our three-person expedition to film a dozen historic Persian gardens. "At this rate, we won't reach Tehran until well past tea."

None of us realized, when we left Kashan this morning, that today's the 20th anniversary of Ayatollah Khomeini’s death. The two-lanes on the northbound side of the highway are choked with vehicles carrying Muslims to Iran’s grandest mausoleum, just south of Tehran, that commemorates the Republic's first Supreme Leader. The mourners are packed into rickety buses and boxy, four-door sedans, none of which has air conditioning or reflects any advances in automotive engineering since the Revolution in 1979. Our pace averages 35 mph. Many families, numbering two to five persons, ride on the handlebars, gas tanks, seats and fenders of single-cylinder motorcycles which, running at open throttle, strain along the road’s disintegrating shoulder at half the speed of other traffic. The women on the motorcycles seem unconcerned that their chadors furiously flap close to wheels and chains.

Fortunately, the air conditioning in Khalil's Peugeot works fine. I couldn't feel safer as he's been like a brother to me since I arrived on my maiden visit to Iran. Khalil did the pre-production groundwork by listening to my goals, arranging a two-week itinerary to distant gardens, and obtaining the sanctions for me to film them. We are returning from the first location shoot.

I slouch in the front passenger seat, absorbed by the monotony out the side window. In the back seat, also from Tehran, is my guide and historian, Dr. Laleh Noorani, a landscape architect and university professor. We have all lapsed into the torpor brought on by the mid-afternoon haze and the drone of the automobile.

The temperature outside is 114 degrees. I’ve never encountered such fiercely dry heat. My sinuses are nearly swollen shut and breathing through my mouth is such a strain that I sound like a respirator. Yesterday's ten hours in the leeching sun may have vaporized half of my body's 60% water component. No wonder the faces of many Iranians look drawn, caved in. Complicating matters is the delirium I feel in my third day of hosting diarrheal drainage.

My two companions, on the other hand, are in good spirits. They pass the time commenting derisively, in Farsi and English, about the poor pilgrims we can’t seem to overtake. For the professional classes, life was better under the Shah's rule before the Revolution deposed him. Only fools would honor either Khomeini’s death or his legacy of a repressive theocracy and moribund economy. Over the privileged, the imperatives of Islam hold less sway.

We pass the outskirts of Qom, Iran's educational center for the mullahs or Islamic clerics. Blonde brick buildings and walls are in shambles. Construction debris and human refuse border the foundations. It is impossible to tell if the structures are in the midst of assembly or disintegration. When the final crumbling facade wipes past my view, a stunning vista of the Dast-e Kavir desert to the east is revealed. Past the parched scrabble of the low, softly sloped hills that rise and fall near the highway, the desert flattens without a break for the next 575 miles before reaching a mountain range. The next town is beyond that. 600 plus miles of blinding blankness without a scrap of vegetation. The food chain climbs no higher than the pores on the surface of gravel and outcrops. I think, This is what is meant by "godforsaken land."

“Look,” Laleh exclaims, “Isn’t that beautiful?” She points to a sliver of white near the horizon, a crack in the desert’s ocher color. “It’s the salt bed of what was once a lake.” I’ll suck anything that doesn’t move is the promise from forces below and above.

I'm the only one to respond. “Very nice.” Torpor returns.

Later, I don’t know how much, I turn forward. Approaching us on either side less than a mile ahead, are two bluffs, 60 or 70 feet high - the divided halves of a hill situated transversely in the path of the highway that cuts through it. The bluff on the left is bare but the bluff on the right is topped by the silhouetted remains of a tree. There isn’t much left - a trunk and the stumps of a few branches. Maybe burnt by a storm, I think. The assessment is quickly erased by a more alert thought: There are no trees out here.

When we get closer to the hills, the frozen shape at the edge of the bluff resembles a human figure on a pedestal - perhaps a statue of a martyred war hero, the sort of memorial common in Iran. We're nearly upon it before I squint in disbelief. Neither judgment is correct. The statue is alive. A man is perched on the back of a donkey. He faces the traffic below and a hard head wind which wraps the loose black fabric of his long-sleeved shirt and pants tightly to the front of his body. He's slender, bearded and barefoot. In spite of the wind, he maintains a balanced composure with hands at his sides. The donkey, equally rigid, is strapped with burlap saddlebags loaded with something bulbous, maybe fruit or vegetables. The man fixes his gaze just over the roofs of passing traffic. The figures and expressions of man and beast are the same - impassive and unflinching.

Although acts of asceticism are often public, my friends have never seen anything like this. Khalil says something to Laleh in Farsi that makes them both laugh. Long after we drive past the bluffs, I stare out the back window and over the line of vehicles. With one exception, all of us are channeled in an unending caravan of overheated mourners on a strand of pavement in a sea of salt and grit. One man registers his opposition. He will move no further. A strip of clothing flaps madly along his spine, like the tattered sail of a lost galley.

Ted Samore ©2002

OBLIVION

From a travel essay about a

solo motorcycle tour of

the Continental Divide.

At the edge of Hotchkiss, population 875, I pull over at a sign I’ve been waiting for. West Elk Mountain Loop. The Loop is a lightly used portion of Colorado State Highway 92 that starts at 5,300 feet elevation and ascends more than 4,000 feet before reaching Crested Butte ninety miles later. From its base I see that the two-lane blacktop is a nominal imposition on the Rocky Mountains’ natural contour. It’s no more than a skinny shelf chiseled diagonally into colossal slopes dense with trees.

At 8:00 a.m. on a day in May, the temperature’s in the mid-sixties, the sky’s partly cloudy, and there’s a slight tailwind. The only sound is a tractor so distant, it’s out of sight.

I’m on the back half of a fourteen-day motorcycle tour of the Continental Divide that has taken me through New Mexico, Colorado, and Wyoming (home is in Texas). I’m riding a BMW K1200, a sport bike capable of breaking every speed limit in the country in first gear. How much of that power I use is assessed at the start of each day. Some days feel right for an aggressive attitude; others are suited for lollygagging. Today, on the West Elk Mountain Loop, I’m up for spirited riding.

The first twenty miles rise at a routine 3-5% gradient through cadent swerves and open corners. My lane is the outer one, away from the mountainside and nearer the valley. A paved shoulder, one to two feet wide, waves along the perimeter. The posted speed limit is 60. I meet only two pickups heading down the mountain so, maybe my wish for sparse traffic will happen.

As elevation increases, the pavement narrows and the shoulder fractures. Ponderosa pines displace elms and sidle closer to the road. Foothills advance their claims on the landscape and crimp the highway into tighter turns.

Timid ascent of a mountain intensifies the dangers because, with a jittery or slow throttle, the motorcyclist loses feel for traction. High speed riding, especially on turns, compresses the bike's suspension and expands the tires' contact patch. Leans grip better.

A diamond sign with a squiggly black line cautions a drop to 45 mph. It’s a breeze at 70. Sharper corners make steering with my arms insufficient. I start throwing body weight off the sides of the saddle to keep the bike in its lane. The tires heat up and get gummier. I link the rhythm of the Loop’s design to yanks of the bike to-and-fro.

The higher I go, the deeper the valley sinks on my right and the closer the mountain wall comes on my left. The contrast gives conflicting notions of speed. An open view of the valley revolves as slowly as a carousel, while opposite, close to the mountain’s rise, it’s a blur.

The shoulders and guardrails disappear. Turns sharpen and speed limits drop to 35 mph or less but I take them at 60.

At around 8,000 feet, the road straightens for a quarter mile so I equalize ear pressure, open the louvers of peripheral vision, and swig the pine-scented air.

I notice gradients are now above 10% and the highway has thinned to where it barely qualifies as two lanes. The white stripe that lined the edge has disintegrated into gravel. After that is a three-foot rim of dirt, then the precipice of the canyon.

Gravel is unmerciful to a leaning motorcycle. Traction is zeroed, the bike falls on its side, and centrifugal forces sweep it in a skid that won’t stop until the bike’s arrested by another natural law.

Moreover, the pavement is scarred. Small clumps of asphalt that filled holes years ago look like chipped cow pies. More scoops were added but they also failed. Longish grass grows in the tar sealed cracks. In sum, the DOT has ceded its fight against the elements. The next sign warns of Falling Rock, which is another way of saying, “Oh well, we tried.”

Left turns take me to cliffs where the tops of sixty-foot trees are level with my boots. Past the treetops and hundreds of feet below is the Black Canyon of the Gunnison River, and past it, a panorama of farmland in two counties. The view vanishes when the road swings back to the mountain face, which comes so close, I can focus only ten yards beyond the front wheel.

A fear surges but not the sort that seizes my throat. This fear complements risky riding by inciting reflexes to fire freakishly fast. Decisions are made with less deliberation than a cat in free fall. Each one is erased by the millisecond. Nothing sticks in the mind because there’s no room for thinking.

I enter a turn marked for 30 mph going 55. Halfway through, a strip of gravel crops up, in line with the wheels’ path. Reflexively, I muscle the bike into a steeper lean, dodging the gravel, but crossing into the opposing lane. A jolt of adrenaline nearly chucks me off the bike. Detonating synapses must be the way doom foreshadows the end. Instantly, I return to my lane, clear of gravel. A moment later, an RV coasts by.

Forwards is a series of five or more switchbacks. I drop into second gear and rev to 9,000 rpms in order to contend with the heaves and thrusts by throttle. The first 180° hairpin is so pinched, I enter and exit like a ricochet. The road’s camber (its slope against the turn) increases vertically until the pavement seems wallpapered to the mountain. I intuit a fit and accelerate above 50 mph. G-forces droop my elbows and pull my head to the tank. Foot pegs scrape. Vision tunnels inside the spin but there’s no dizziness. The climb refuses to quit and I'm doing things with a motorcycle I never thought possible.

The pitch slacks and the bike gains buoyancy. As if on cue, the sun makes a showy entrance atop a peak dead ahead. Light pierces the clouds seeming to consecrate the world below. Maybe Bierstadt’s 19th Century paintings of the American frontier weren’t idealized.

Parallel to my right and less than a mile away, another mountain range comes into view. It’s perhaps a thousand feet lower, with peaks that mirror the ones I’m riding. Between the two ranges is the enormous cavity of the Black Canyon. In and out I zoom until at the apex of one turn, the base of the cavity appears. It’s the Blue Mesa Reservoir with blue water tinted so richly green, it could be off the coast of Yucatán. A forested bowl rises sharply from the shore. The lake is serene, the reverse of the turbulence I feel high above.

Through the next corner and the next, I sense a pinnacle but the road keeps climbing. I’m on a musical legato wherein the pitch rises to the limit of hearing. Suddenly, halfway through a left turn, the pitch steadies. I’ve reached the summit and before me is a void − no trees, no ground, only sky. The road has been an acceleration ramp to this climax, the terminus of the crescendo and thinning air. An impulse, as strong as any I've known, urges me to spike the throttle and launch into the firmament. Another impulse squeezes the brakes.

I stop at the corner’s edge and get off the bike. After shedding the helmet, I feel my senses return. The air’s dry and crisp. Respiration becomes a conscious act. A breeze murmurs under my breathing. There’s nothing more to face and in the stillness, I let the body align.

At 9,875 feet, the perch is taller than the shorter mountain range on the other side. Beyond is a mesa without end. At the horizon, the pale green earth fades to a vapor that merges with a smear of altostratus clouds, white as snowcaps. I've breached a membrane to enter a domain of deities.

As abruptly as my spirit sank at the chance of a catastrophe, it is lifted by the sublime. Mortality juxtaposed with eternity. I’m introduced to a new realm of confidence and of humility. Home is still six days distant but there is no longing.

IN THE COMPANY OF ORIGIN

Observations from

a Chilean glacier.

The wind was howling the afternoon I met Huentes Tours' lead guide, Robert, at a lakeside hut. His poco English was better than my poco Spanish so, he gave me the basics in English. To register for tomorrow's hike on Glaciar Exploradores, I must pay 40,000 pesos ($65) and put my name on a list. There was no liability release form and no advice on prep.

"We give you crampons, mitts, lunch," said Robert loudly. "Leave at 900 hours, back at 1800. Write your age here."

"What do you think?" I said.

"45."

"Deal," I said, getting a laugh.

The next morning was overcast, temperature in the mid-60s. On the walk from hotel to Huentes' hut only stray dogs stirred. At 9:00 our crew (2 guides, 8 guests) materialized and we threw our backpacks and selves into a worn minivan. They would speak Spanish for all of the tour. I understood next to none of it.

We headed west up Valle Exploradores on a 2-way gravel road that was, more or less, one lane with skinny shoulders. The blind corners, rutted dirt, and scarce signage tempered not the driver's incaution. I used my failsafe worry suppressant - acceptance of futility - and gazed out the windows.

The drive was akin to being inside a continuum of a natural history museum, one that depicts a land's development over millennia. Only this continuum moved backward in time. As we drove, the landscape returned to the dawn of its creation. In 50 miles, millions of years of change unwound.

At first the rivers were clear and the lakes were royal blue. 30-60 foot ash and beech trees thrived from the shorelines to the highest elevations (8-9,000 feet). 15 miles into the valley, mountaintops became bare and tree lines were introduced which, further on, slowly erased lower and lower. As the road climbed, the sun came out. Lodgepole pine trees poked up with the confidence of a species that would eventually prevail. From contrasting directions, rivers surged. They were turning the gray of baked clay. Green tinged the lakes' blue. Topsoil thinned. Shrubbery, ferns and grasses displaced forests. Soft shouldered mountains grew saw-toothed peaks and giant cliff faces. Waterfalls punctured the high walls. Light rain squalls rolled over us.

Suddenly the minivan stopped. Robert hollered back at the passengers, instructions I supposed. All I got was aqui. We piled out and were handed wads of gear and a lunch sack. Minutes later, off we trudged.

The forest's canopy shielded us from the wind blowing down from the glacier. A soggy single track trail bumped steadily upward. Then switchbacks kicked in - narrow, steep and erratic. We slipped on roots and ducked low branches but the pace was agreeable. I hadn't a clue about the route or what lay ahead.

We entered an expansive floodplain punched with shallow pools called kettles. We skirted around the floodplain then over a gentle rise of grasses in hard dirt and through a patch of alluvial mud to where the vegetation and the trail ended. In one hour we were on the threshold of the moraines.

Not until then did I notice the mountains had retreated to a 360° cirque. We found ourselves in the center of a valley a mile and a half wide. Amassed in the valley were chaotic rows of stony hulks. Known as drumlins, they're made of glacial till - boulders and rocks - in sizes ranging from looting bricks to bank safes. The breadth and discord of colors and shapes had no discernible source and absolutely no fit. The rubble looked like the aftermath of an explosion with no epicenter. A god had kicked the hell out of his construction set. There was no way around it. Clambering over the debris would put me face to face with the beast that created all I'd seen today.

Temperature had dropped 10 degrees. Clouds were lowering and dripping sprinkles. We set off but no longer in a single file. Each hiker found his own path and pace and I felt the first collective chill of doubt. That the boulders had achieved at least a provisional balance, we took on faith. A person's weight could alter it just enough to make the slog skittish. The bigger the stone, the less it moved. I plotted my steps four at a time to quickly get off the wobbly ones. No plane was horizontal or boot sized for predictable purchase. The ankles took a beating.

20 feet in front of me someone stumbled. In falling, his arm dropped into a gap between the stones. A guide pulled him out and settled his fright. Minutes later, from behind, I heard a woman yelp. She'd cut her hands trying to catch a fall. I gave her my gloves. Thence, I learned that rock to rock, the grit had no consistency. Edges were sharp as if recently fractured.

I didn't mind the work. Passage to a glacier should have a toll. Often I paused to catch my breath and take it all in. The panorama was beautifully bewildering, especially in the 30 foot deep hollows. How do you navigate your way out? Robert forged ahead but not so far that his red jacket couldn't be seen cresting the mounds. Up and down a mile of drumlins I climbed, dodging spills. My first impression of this space as ruin was wrong. This was, in fact, a foundation for something new. Coincidentally, I realized something about the thunder I'd heard since the hike began. It was actually rock fall.

The boulder field faded into gravel and sand as we reached the melting rim of the glacial snout. It was littered with small sharp stones like the cut glass cemented to tops of barrier walls. Sediment blown across the ice peppered its white ridges brown. In the slivered beds of rivulets were hints of a supernatural blue. The low cloud ceiling could not conceal the unmistakable blue of a glacier that glowed as if from a buried light. I looked up for my first clear view of Exploradores, probably 3 miles away. Its swath of scratched porcelain, of unfathomable gravity, was cradled by two mountains. Further on it curved to the right, behind the shoulder of one.

As expected, the glacier's heft was astonishing, but its composure was transfixing. At first, I did not move - stillness was right reverence in its presence. Everything else - the ring of mountains cloaked in a million trees, the spouts of falling water, thewind, the pinging rain, my panting - was subsumed by the glacier's imposing silence. Knowing the nil of my moment upon its eons of being did not make the moment any less profound. I whispered an invocation and imagined another voice in return. All in good time.

It was almost noon and the temperature was in the 40s. Robert gathered the hikers to show us how to strap on crampons and gaiters. We sat on the slush. Though the spikes were bent and the straps were ripped, the crampons would make walking on ice safer. Last, we put on insulated mitts. We were set to explore the glacier's terminus zone for two hours - ample time but not enough to reach it's ablation wall where the net loss of mass occurs.

The group adopted an expeditionary line but I rambled away. My crampons easily grabbed the ice which was porous with brittle strands of crystals. In a half mile the dark rocks and sediment had all but vacated the terminus zone. What remained was a sea of whites and blues, the colors of water's transfiguration. Turning in a deliberate circle, I saw all the stages of melt and recession in the lifts and falls. Underfoot, at depths and in ways I could not imagine, was the grind of originating a landscape. I saw only the armor. Further on the field's rolls eroded into arêtes, valleys and spurs. Every guttered white decline was striated in powder blue. I estimated the angle of drop-off to be from 30° to 60°. I zigzagged to avoid slopes and stay on ridges.

The space started expanding - downward. The arêtes stayed relatively even as ravines sank to narrow them. Stunning cavities appeared at lower levels. The melt had bored beneath the frozen surface like a decay and opened tunnels big enough to enter. Or fall into from the bridges above.

I was bewitched by crevasses and seracs. I chose paths to be surrounded by them, though gauging the scale was difficult in ill-defined light. The slopes were sharper and deeper than they looked at first. Some fell away 50 feet or more. The cracks that pierced deepest unveiled upright ovals of cobalt blue. From high perspectives I saw dozens of these pockets interrupting the diagonal striations. Small and large, they resembled nothing so much as pudenda. Behind them were forces I'd never know and probably shouldn't confront. I thought of them as naked portals to the promise of life.

As I walked I knew that I was in the spectral company of violence. On another day, in the cold and brutish weather that is most common, there'd be danger in extremis. Frostbite, broken limbs and death occur in the vicinity of glaciers. Moreover, there was the constant corrosive violence of tectonics and recession, measured in centimeters and over millennia. Yet nothing in this window of time felt forbidding. The rain had turned to mist and the air was windless. I was granted serenity. I could have wandered for hours.

On a ridge top 100 yards ahead, the nine others had stopped. By the time I joined them, they were halfway through lunch. I dug into mine. We were within 1 mile of the ablation wall. Damn fine place to grab grub. It did not escape me that what I saw as rare marvel was actually a Patagonian banality. Spectacles are a commonplace in this part of the world. The rarity is the observer.

It was 2:00, time to turn back. No one talked as they shambled; all were exhausted. It was, more or less, the same route we took out. Even so, I loved seeing things in reverse, under different light and with the chance to listen again. I'd knew I'd never return. Occasionally, I stopped to look back at Exploradores. On one turn, before re-crossing the drumlins, a rainbow appeared over the frozen sea I'd walked. I took my final photo and stowed the camera.

Ted Samore ©2015

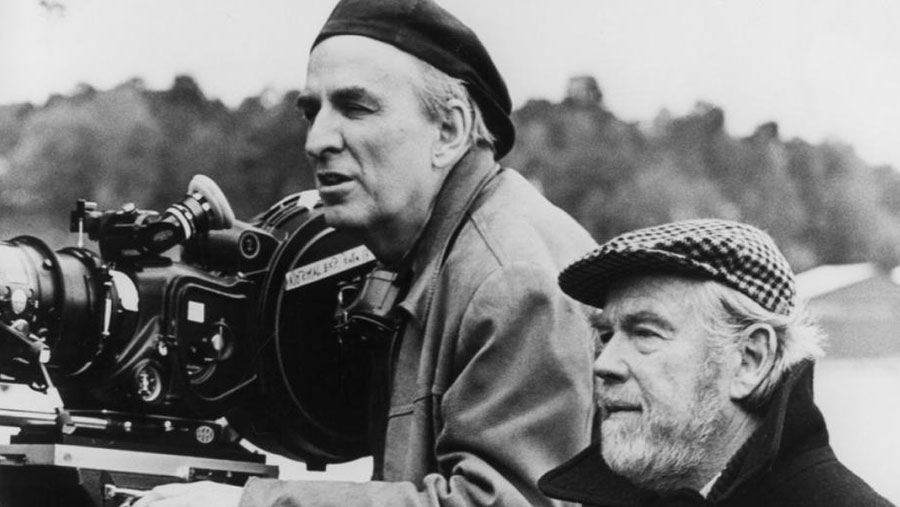

ON BERGMAN

Bergman was both inspiration

and aspiration.

My esteem for Ingmar Bergman's films is boundless. No other director's work penetrated as deeply or lingered as long. He probed the ways external events impelled internal journeys. Who else did so many variations of that theme and stirred international audiences so profoundly?

Bergman's creative output over almost sixty years coincided with a window of time when the gods of cinema allowed the realization and distribution of his art. That his actors performed with such consistent and unalloyed intimacy confounds anyone who makes movies. Why? Because the contraptions, expense, temperaments, and folderol of production convolute in ways that undermine discernment and concentration.

I learned of Bergman's death in 2007, the morning after I'd watched his final film, Saraband, released four years earlier. The nuanced lighting, plain composition, and spare editing gave the characters no reprieve from each other or from themselves. In a signature Bergman monologue, the central figure, Johan, speaks of his crisis of faith as his death looms. When he finishes, he finds an epiphany. "Maybe it'll be easier than I thought. I'll just step into it." That was the image of Bergman I held at his end.

How curious that a Swedish director grabbed hold of me, a Midwestern kid, at the age of eighteen. While a freshman at the University of Northern Iowa in 1970, I saw Through a Glass Darkly. As often happens to first-time viewers of Bergman, the experience was unsettling and transfixing. Afterward I walked around in a daze until I found someone to talk with. It was an early lesson in serious cinema: discussion is the best way to decipher themes and their effect on you.

Bergman hit his popular and creative prime as I moved through early adulthood. In most American cities Shame, Passion of Anna, and Scenes from a Marriage played on multiple screens. Hard to believe that in Minneapolis, when I attended a Wednesday showing of Cries and Whispers released three weeks earlier, I waited in line to get into a sold-out house.

Years later, by providence, I met the man. Bergman was in Dallas to accept the Meadows Prize and a large sum of kronor from Southern Methodist University. For three days, he was available and affable in seminars with students. I attended every one and at a reception, we chatted.

To set the stage for his visit, SMU screened twenty-five of his films in the six weeks prior to his arrival. I went to all. Until then I’d never seen his comedies or romances. They were as great as the psychodramas that followed.

My girlfriend at the time had no exposure to Bergman, and she joined me for half of the films. For hours we talked about each film, and not sadly. We examined the relationships on the screen, the tangents off the screen, and the personal reflections the films provoked. They guided us to emotions and realizations which otherwise would not have been expressed.

Without flinching, Bergman depicted what we'd rather dodge – the psychic tug-of-war between our flaws, our ideals, and our longings. Given the despair and isolation of his central characters, many saw fatalism at the core of his films. Bergman might have said he was coming to grips with his demons. My girlfriend and I thought his work permitted us to confess, to plead, and to imagine what follows the stripping of a soul. In short, his films led us to love. During the months surrounding Bergman's visit we were never closer.

Feature films have changed. Now they're digitized and democratized. Inexpensive cameras capture fine images in found lighting. Anyone with a laptop, a smartphone, and time on their hands is a moviemaker. The longer I’ve been in the business, the fewer film people I meet who are enthused about or aware of Bergman's body of work. There remain only a few directors who practice Bergman's style.

Bergman, Antonioni, and their contemporaries came from writing and/or theatrical traditions. Top directors today, especially Americans, are schooled in advertising, music-video, or fix-it-in-post. In Bergman's films, time's passage and its emphasis were dictated by character. Now time is shaped by tapping audience prompts. The accomplishments of various departments – cinematography, sound design, art direction, computer graphics, postproduction – have never been more polished. When blended and presented in good theaters, the results are breathtaking.

Bergman and his collaborators devoted energy and soul elsewhere – to script and to performance at the moment of capture on a set. Editing was simple assemblage. Music scores were supplementary. On the screen their bravery, their rigor, were openly tangible. Audiences today don't want the bother. It was my good fortune to be alive and receptive when Bergman's genius was given first light.

Ted Samore ©2021

THE ROAD AWAY

He's now eighteen and so ends the most crucial part of my one shot at parenting.

The day of my son's birth, I held in my hands an angel with boundless possibilities. I felt the promise of a profound calling without a hint of dread. We had eighteen years to perform spells on each other.

In two days I will deliver the same boy, my only child, to his freshman year in college. During the summer-long empty nest countdown, I'd kept an even bearing. Now packing his things, I felt peevish.

My wife, Susan, and son, Griffith, laid out things in the house while I jammed the bulk of his material world into our SUV. Starting with the roof carrier, I put in bundles of soft items.

A month earlier an inexpressible sadness had infiltrated my psyche. Alone in the driveway, it consumed me. A terminus was at hand and I was buckling. This was the official commencement of my son's independence and adulthood—something you surely see coming but are still unprepared for, defenseless.

After filling the roof carrier, I moved to the trunk. First in, a mini-fridge—standard fare, I'm told, but in my opinion, unnecessary.

Next was Griff's most prized possession: his desktop computer. He'd custom built it from scratch according to his specs, no one else's. The project took him weeks and the result was big pride for us all. I placed soft material around the PC to protect it against jostling.

In the early years, after putting Griff to bed, I often asked myself, "Did this dear boy have a wondrous day? Did he take in all he could? Was I present?" I don't think I ever answered no and watching him grow, I'm pretty sure he agreed. With his teen years my long run of satisfaction clotted as many bedtime reflections were not sweet. He'd had a bruising day or I'd shone a tin ear or lost my temper. What came back to me was chilly resentment.

I finished the first layer of stuff in the trunk with boxes of books. Essential was Griff's collection of Dungeons and Dragons handbooks. He added some science fiction, young adult satire, and reference books for math and science. Also in the stack was the "library starter kit" I'd given him which included a dictionary, a book of poetry, and novels that shook my early college life to the core.

From our repository of sporting goods, Griff wanted two things: a frisbee and a fox-tail throwing toy. The frisbee had been with me for almost 30 years. The fox-tail was a birthday gift we gave him long ago.

Is there an indulgence more joyous and deserving than your child's birthday? We heralded each of Griff's with themed parties and gifts that thrilled because our choices were spot on. For his sixth, we gave him the only pet he'd ever ask for—a tarantula. We were shocked to learn later that the spider was female and might live twenty years. We joked that he'd be taking her to college though we couldn't imagine Griff or the tarantula that far on. Jadis is now twelve and she'll stay behind.

I remembered how, the day after his birthdays, an inner voice would pipe up, "He's five. I have thirteen years left." When Griff turned nine, it got more serious. "I'm halfway there. Thank goodness there's still another half to go." Now that he's eighteen, so ends the most crucial part of my one shot at parenting.

With every relationship I've known, reciprocity at some point played a part. Being father to this boy, reciprocity never crossed my mind. His happiness, his self awareness and confidence, his friendships, and finding his best fit in any environment—to me these goals were self-evident and supreme.

Griff's departure makes a vestige of these devotional tools. The lickety-split feedback loop we'd honed would sputter from disuse. What of the things I'd tried to represent? Giving, listening, empathy, fidelity, rational thinking, righting mistakes. He was the only one who paid scrupulous attention. I would lose his judgment and its remedial clout. I would be less motivated to take on the steady stream of quotidian concerns. He compelled me to care and stiffened my backbone against anything or anyone that pinched his freedom or well being.

It is possible that for the past three years Griff had tried to ease the transition for me. In some manner his blooming adolescent appetites had schooled me in the pulling away. He'd already decoupled. But on the eve of our separation, I felt the pain of a sudden excision.

The SUV still had room for more compact and flexible things. I put in PC peripherals, perishables, bike gear, shoes, and clothing including Griff's first tailored suit. By 6:00 p.m. we were 95% packed. We unwound with a home cooked meal and watched an hour or so of video that Griff shot on his summer trip to Spain. Then, as per routine, we went to bed. I stayed up a little later to sit on the porch, assess the day's labor, and have a short cry.

I woke at 7:00 a.m. Our target departure was in an hour and a half and the only things left to throw in were three overnight bags and a bicycle on the hitch.

Griff was up and moving before I was. "Dad, I'm nearly done with my backpack. Tell me what's next."

A call from his room without me having to wake him? Volunteering to help? I needed a minute to muffle the urge to cry and went to the kitchen for a glass of orange juice. Our home was oddly still.

My eyes filled to bursting. Our sunny trio (his label for our family) would no longer be conjoined under one roof. Facing us on the passage to whatever is next was not a bridge but an iceberg. I found Susan in the living room with her back to me. Without a word I turned her around, pulled her to a tight hug, and wept into her shoulder.

She reacted as if I'd broken something. "What's the matter? Are you okay?" she asked.

"It's over," I said, twice.

Instantly she understood my upset but wanted no part of it. There were the practicalities of making a dorm room habitable.

"He'll only be five hours away," she said. "We'll still see him every few weeks. He may not even like this college and we'll have to do something else..." I stopped listening and collected myself once more. This time it held.

By 8:45 a.m. everything was stowed. Like puzzle pieces we dropped into our car's seats. The assembly gave me a provisional composure despite not having a clue what was ahead. This would be our first journey in which only two returned. We drove away, as if it were the start of another family vacation.

Ted Samore ©2021

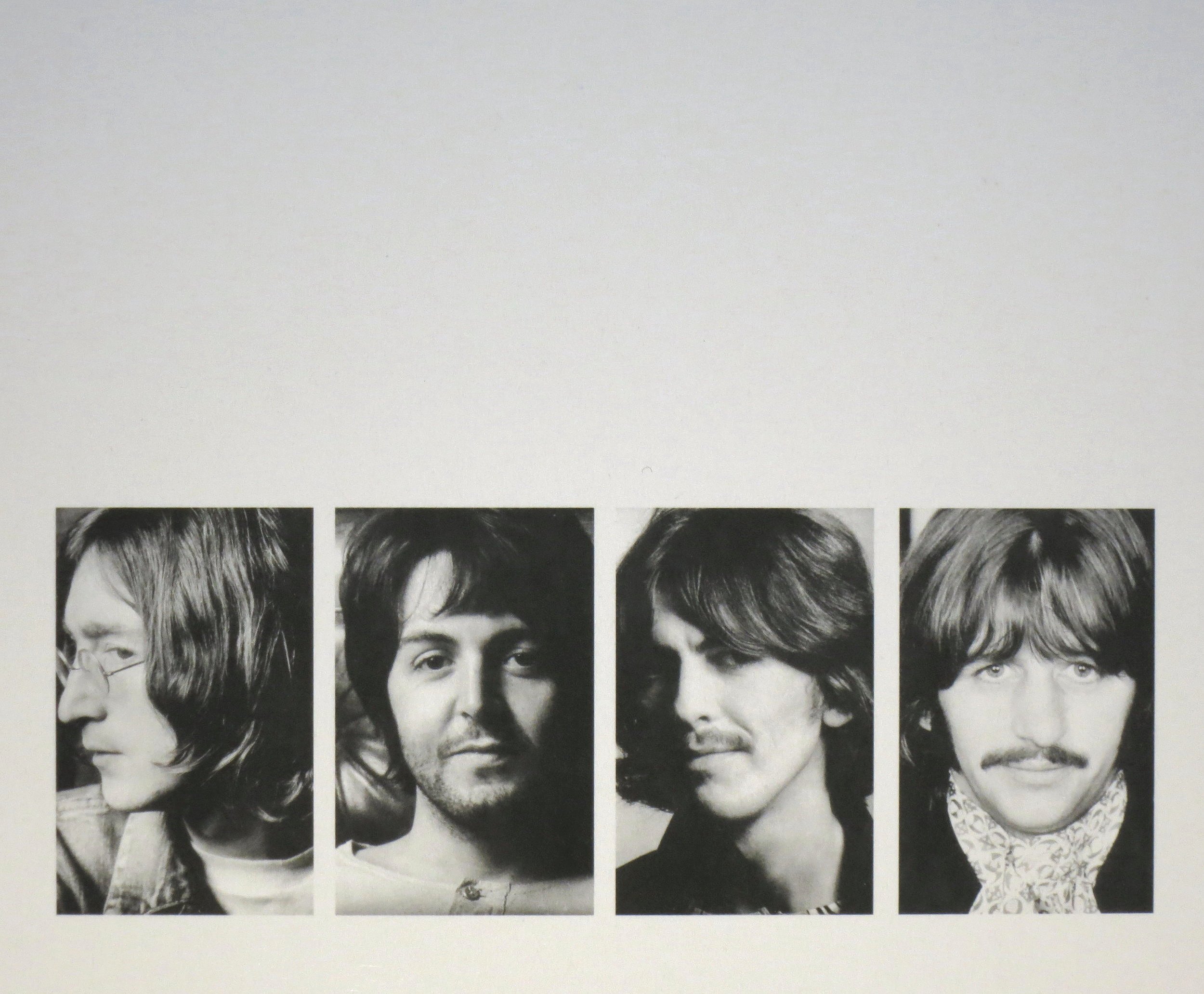

REFLECTIONS ON THE WHITE ALBUM

On Giles Martin’s 50th Anniversary re-mix of a favorite.

When the 50th Anniversary edition of The White Album arrives, it will be my seventh or eighth copy. Why get another? Because Giles Martin ran this re-mix and there's no one with better tools and better acuity for Beatles music.

I remember buying the original vinyl version as a sophomore in high school in Iowa. I was shopping for something else at Belles Hess, a sort of K-Mart, when I spied a freestanding cardboard display absent any word or icon. It held two rows of white LPs. Up close I discovered two small embossed words, low and off center. “The BEATLES” It was as unremarkable as the stamp of an inch on a ruler but it made my brain pop. What the blank? Below and smaller was a gray six-digit number that looked like a misplaced cataloging ID.

I followed many bands back then but was devout only with the Beatles. They were like brothers in absentia. With each release my commitment deepened despite friends hopping off at the Magical Mystery Tour. That I was clueless about what the Beatles had been doing wasn't my fault. There was no ubiquitous multi-level marketing, no internet share-steal-gossip, no FM rock radio, no Rolling Stone magazine. The White Album arrived out of the blue without so much as a single for us transistor radio users.

The album had two discs but no song list. I prayed it wasn't a greatest hits collection - a sure knell for a band's exhausted creativity. I took the chance and bought it.

I played it at home for my four natural brothers but stopped because they weren't paying close enough attention. So, I took the portable hi-fi with its fold down turntable to the basement for private listening. (Hearing an album's first play while stoned was still a year or two off.)

On previous releases, each Beatle had been gradually staking claims to his own turf. On The White Album each was up to defending his turf. Here the writers' POVs were distinctly evident. I was unprepared for the jumps in mood and arrangement. The music moved from disjointed to intimate to brutish. I thought the Beatles were saying, we will rend you of sweetness but from the remnants, we'll make something purer, more vital. The first listen both hooked and disquieted me. Never had I heard beauty and beast dwell together so starkly and comfortably.

Soon the outside world had its say. Paul-is-dead clues were deciphered and concocted. Authorship and players were misattributed. The splintering of the four was inescapable.

In the next year there came Manson's depravities and a miracle of reconciliation, Abbey Road. Then the Beatles disbanded. Curiosities followed.

Lennon resorted to primal screams. Starr became a vaudevillian. Harrison ceded his mantle to Jeff Lynne, an imposter. McCartney sentenced himself to playing in an average Beatles cover band.

There were two other occurrences as yet overlooked by historians. In the first, I was fired from a disc jockey job for playing "Martha My Dear." In the second, my college thesis's soundtrack included my only film use of a Beatles' song (still the best cinematic appropriation of "Mother Nature's Son").

I've listened to a ton of music in the fifty years since The White Album's release and it's never been displaced from the top five of my desert-island list. More than any Beatles' work, I've returned to it to receive and perceive more. It's been an important companion to me, as a teenager and as a father.

"Good Night" is an example. From first hearing to this day, tears can well when I think of all the song's associations. It was one of many lullabies I sang to my baby boy. Tellingly, it was the only one that he, in his prelinguistic state, chose to hum with me.

Every loving parent knows that ushering his child into safe sleep is a tender moment. Lennon, that caustic Teddy Boy, gave me an instrument for just that. And he gave my son a gracious portal to his dreams. The song, like the rest on The White Album, is an achievement in timelessness.

Ted Samore ©2020